Summary

About my two spontaneous hybrid plants with orange pollen

My Observations about Cultivars of Basils

Regarding the spontaneous crosses involving “Kapura”, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, and Ocimum basilicum

Mischievous Whistle-Singing!

Predominance of Linalool in Basil and Cannabis… For the People’s Sedation?

Is it a coincidence that in France, and in many countries in the Western world, the only type of Basil sold – with the exception of small niches in the market – is Basil, of the species Ocimum basilicum, with a predominant chemotype in Linalool?

Indeed, depending on the growing and drying conditions, and the time of harvest, certain varieties of green-leafed Basil (such as “Genovese”, “Grec/Griega a Palla”, “Prospera”, “Devotion”, “Obsession”…) or purple-leafed Basil (such as “Rubin”, “Osmin”, “Rosie”, “Dark Opal”…) can contain up to 75% Linalool in their essential oil.

Or is it because Linalool is characterized by its reputation, and properties, of being a substance that provides calmness, good mood, alleviation of depression, sleep, sedation, etc? And furthermore, is it because Linalool would be the therapeutic substance, par excellence, for all those suffering from a bipolar mental chaos, Link, who, according to some studies, constitute up to 6.5% of the population?

This is very good news because, in light of the graphenization of the brain, a large part of the human population – which has lost, dramatically, its way and can not return to the Mother/Earth – we will soon witness a pandemic of tri-polar, quadri-polar people… And this is not to mention the considerable damage to the human psyche generated by the state of permanent “cognitive dissonance” orchestrated, continuously, by the Globalists and other perpetrators of Social Evil.

Is it, therefore, to appease, lull, calm, sedate the Western Peoples – because the social melting-pot is always on the verge of exploding – that their most consumed aromatic plant, Basil, is marketed and promoted through varieties whose chemotype is mainly characterized by a soporific terpene, Linalool?

Is it, likewise, to soothe, lull, calm, sedate the Western Peoples that the most marketed “cultivars” (meaning “commercial denominations”) of THC Cannabis – and, also, the most “feminized” and trafficked ones – have, as their predominant chemotype, two sedative and soporific terpenes, Linalool and Myrcene?

Moreover, Linalool has the reputation of being a cannabinoid elicitor. It acts, synergistically, with cannabinoids, enhancing their therapeutic impact – in light of the famous “Entourage Effect”, recently discovered by PhD scientists whose mission is to re-invent lukewarm water!

Are they, by the way, also, Linalool-type varieties that are promoted in the, uncontrolled, sector of CBD Cannabis?

In any case, what is not put into question is the more than potential – and legalized – presence of fungicides in Basil, marketed by chemical agriculture, due to the severity of the contamination of Basil by the downy mildew, Peronospora belbahrii, which is lethal, for the Basil plants, in many regions… including France.

According to the RAP French organization, these fungicides are based on the following 5 authorized active substances: mandipropamide, oxathiapiproline, cyazofamide, phosphorous acids, and fluopicolide. What about their toxicity? No worries, according to the reassuring Authorities, as they would not pose any risk of cancer induction – for example. Really?

My Basil-Perfumed Wishes

Caveat. This “Basils 2025” project is a continuation of my “Basil Projects”, namely, my extensive writing work on Ocimum Medicinal Monographs, since 2022, and my various experimental gardens in 2017, 2018, and 2022 – in Costa Rica, Oregon and Spain – not to mention the preparation of extremely medicinal Mother Tinctures! I have been passionate about Basil since our first organic seed production gardens in St-Menoux, France, in 1993, and then our seed production gardens with “Annadana” – a seed-bank I funded, in 2000, with Stephane Fayon, in Auroville, Tamil Nadu, India, which was active until 2012.

Caveat. This “First Report” – with all pictures from Xochi – has been written in French and I have no time, presently, to realize the full English translation myself… because it seldom rains and I need to water our huge garden daily. However, I do correct the robot when it errs – or when I dislike its rendering… which is very often! Then, I do translate, myself, the passages, of this report, which are too subtle for the Archontic machinery of the Artificial non-Intelligence… devoid of any authentic “sensation“… which is the most mysterious element of natural science – as Wilhelm Reich once asserted it.

Before presenting an initial assessment and the objectives of my “Basils 2025” project, I would like to:

1. Make everyone aware – and indeed every human being who cares about the harmonious functioning of his physical and psychic health – that Medicinal Plants represent the “Future Primitive” of Human Health, and that the botanical archetype “Basil/Tulsi/Ocimum” is part of this…

Moreover, Basil is one of the most important Master Medicinal Plants – in all aspects, cultivars, ecotypes and species – for the sake of a natural therapeutic and pharmacy… just as it is the first aromatic plant to be cultivated and marketed in many countries around the world. This is why it is referred to as “Royal.”

Tulsi Tulana Nasti Ataeva Tulasi”. “Tulasi is Incomparable”… in the sense that it cannot be compared to anything else. Because of this attribute, it is a manifestation of the Heavenly Mother on Earth. In Hindu mythology, Tulasi is an avatar of Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu.

2. Regenerate the collection of Basils, Tulsi, and other Ocimum cultivars, sold as certified organic seeds by the Kokopelli Association, in terms of diversity and specificity – as I will explain further. Today, Kokopelli, in France, offers the most diverse range of organic Basil seeds on the planet.

This is not a rumor but a fact – and, in many ways, quite an achievement! As we have been persecuted by the French Authorities, and their minions, for so many years, under the comical pretext of “non-legality”.

I introduced part of the Basil collection, sold by Kokopelli, with the first Terre de Semences catalog in 1994, which featured 12 Basils including Ocimum kilimandscharicum, Ocimum campechianum, and the temperate Tulsi, presented, at that time, as “Holy Basil” and, mistakenly, as Ocimum tenuiflorum/sanctum.

As a reminder, it was that year that Michel Chauvet, director of the Genetic Resources Office, politely advised me to abandon my Quest for Food Biodiversity – and mind my own business – because family gardeners “already” had ten cultivars of red, non-hybrid tomatoes authorized by the GNIS Official Catalog!

In 1994, Terre de Semences was already selling certified organic seeds of 591 cultivars of vegetables, cereals, herbs, flowers, and medicinal plants – including 130 cultivars of tomatoes. Today, 32 years later, hundreds of tomato cultivars are available from Kokopelli – in all the colors of the Rainbow… that is, the Rainbow of colors, not of woke ideologies.

Thus, I introduced, myself, along the years, the full collection of “Basilics and Tulsis” proposed, now, by Kokopelli. Nonetheless, some of them I introduced for the sake of “diversity” without really knowing their value, and necessity, in the gardens… and, what’s more, without really knowing the authenticity of their existence – in the case of duplicates and other fanciful commercial names. One need only compare the names of the Basil cultivars in the Kokopelli, Richter Seeds, Baumaux, Ducrettet, etc. ranges to realize that the Diversity of Basils is also plethoric when it comes to “uncontrolled appellations of origin”!

I would, therefore, like to refine it while diversifying it even further – for example, by incorporating geographically certified ecotypes from a specific People and Land – and also, more essentially, by characterizing its chemotype for the “Future Primitive” of a safe “Family/Home Pharmacy”.

In 2017, in Costa Rica, and in 2018, in Oregon, I cultivated a number of Basil cultivars, including around twenty from the Canadian seed company Richters Seeds, as well as ecotypes of the species Ocimum tenuiflorum, Ocimum gratissimum, and Ocimum selloi/carnosum. In southern Oregon, we lived 50 meters form the Applegate river, but with temperatures exceeding 40°C in summer – a Paradise for Ganja!

In 2022, in Spain, in our garden at Casa Kalika, I grew around thirty types of Basils – including some from Kokopelli – also in a relatively desert-like biotope… and a very warm one, atmospherically speaking!

This year is the first time I have had the opportunity to grow the entire range of Kokopelli Basil cultivars at the same time – at least those available in December 2024. So I can already draw some initial conclusions – especially regarding the Ocimum basilicum cultivars, most of which were already well developed by mid-June… thanks to our geographical location.

3. Highlight the fact that the Kokopelli Association sells organic seeds of Basil cultivars that are resistant to downy mildew – even if, in some cases, this resistance is only relative, depending on the strains of Peronospora belbahrii.

It would be very interesting to launch a survey on the possible prevalence of mildew in Family and Home Gardening in France.

The Kokopelli range includes 3 cultivars of Ocimum basilicum that should be promoted in view of this pathology: “Dévotion,” “Obsession,” and “Mrihani.” The first two are recent developments from Rutgers University in the US, while “Mrihani” is the only ecotype (native to Zanzibar) of Ocimum basilicum in the world that is 100% resistant to downy mildew. Unfortunately, its leaf appearance is unusual and, more importantly, its main chemotype is Estragole (Methyl Chavicol) – not Linalool or Eugenol, which are more popular with consumers.

Organic vegetable growers, in France, continue to lose their conventional cultivars of Basil (Genovese type) from June onwards, due to attacks by downy mildew – without ever having grown and evaluated the “Dévotion” and “Obsession” cultivars.

It is as if there were a veil in France over the reality of downy mildew destroying the Ocimum basilicum species. Among professionals and inter-professional organizations, we are somewhat confronted with a code of silence – and wishful thinking!

It would also be very interesting to conduct a study on the feasibility of growing more tropical species of Basils, depending on the region of France, since all major species of basil – with the exception of Ocimum basilicum – are either completely resistant or highly resistant to downy mildew. The aim would be to increase access to key Master Medicinal Plants for the Family Pharmaceutical Treasure-Chest.

There is also an “Opalescent” selection – from Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seeds in Oregon – which the Kokopelli Association sells. Today, Frank Morton is working on his F6 selection of this cross involving the “Mrihani” and “Dark Opal” ecotypes – in an attempt to incorporate “Mrihani’s” total resistance to downy mildew.

It would therefore be interesting for Organic vegetable growers to evaluate this new “Opalescent” selection in vivo, bearing in mind that it would also be desirable to select for a Linalool chemotype rather than an Estragole chemotype.

4. Overcome the apathy, contempt, inertia, and nonsense that currently plague part of the research community studying the Ocimum genus – and, by extension, all seed companies around the world.

One day, perhaps, I will publish my highly amusing and distressing written exchanges with a “geneticist” from Ethiopia, for example, or with the small world of “botanists” in northern India… regarding my discoveries concerning the existence, as a species, and the Ethiopian origin, of the “Temperate Tulsi”, the Besobila, Ocimum bisabolenum.

About my two spontaneous hybrid plants with orange pollen

Regarding my two spontaneous hybrid plants with orange pollen, involving Ocimum basilicum and, presumably, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, based on the color of the pollen, cold resistance, floral morphology, and, above all, the enormous size of the plant – because in temperate/subtropical climates, Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants can reach over two meters in height.

A gift from Mother Earth! Especially since part of the genetic transfer could involve resistance to basil downy mildew, Peronospora belbahrii.

The first enormous plant – over a meter wide – did not survive being dug up, in the fall of 2024, from a very compacted path in the garden… where it had once grown spontaneously. We did, however, manage to save a cutting – which grew over the months – that, like the mother plant, has branches with white flowers and branches with purple flowers – a rarity…

…and another gift from Mother Earth!

The second spontaneous cross – which I had transplanted into a pot when it was young during the summer – spent the winter on a covered balcony, but with very little protection from the wind. It therefore withstood temperatures of around -7°C and, above all, a four-day period of freezing fog, which destroys leaf tissue. Beginning of July, this plant was, already, over 1 meter in diameter and has an exquisite fragrance…

… which is reminiscent of the “Cinnamon” and “Licorice” cultivars! It is therefore quite possible that this spontaneous, gigantic cross has a chemotype predominantly composed of methyl cinnamate. It would be very exciting, indeed, to introduce – by cuttings, so far – a perennial Cinnamon Basil with a large development, resistant to cold… and perhaps even resistant to mildew!

The winter weather conditions were such that none of my Ocimum bisabolenum plants survived—unlike in previous winters, which were just as cold but without freezing fog. However, my only Ocimum kilimandsharicum plant survived the entire winter.

We live at an altitude of 550 meters in Spain, with a splendid view but, on the downside, with strong winds that often reach 60/70 km/hour – but, above all, can last for days… or weeks. It reminds me of the Kali Gandaki valley in Mustang…

To give you an idea of some of our very special “biospheric” conditions: this year, I planted potatoes in early January – against the advice of local farmers, who do so around mid-March – and in early May, I harvested nearly 50 kg of new, delicious potatoes that had survived the frosts.

At the end of this Report, I will comment the diverse spontaneous crosses I got, this year, involving Ocimum kilimandscharicum and, presumably, Ocimum basilicum.

More than 80 accessions of Basil, Tulsi, and other Ocimum species, in our Garden at Casa Kalika in 2025

In the spring, we installed mini wall greenhouses and I sowed more than 80 accessions of basil – species and cultivars – in seed trays. Namely:

The Kokopelli collection available in December 2024.

26 accessions from the GRIN /USDA.

Cultivars from Richter Seeds in Canada.

My own 2022 crops involving the relatively mildew-resistant cultivar “Devotion,” the Turkish ecotype “Esfahan” of Ocimum americanum var. pilosum, and my various ecotypes of Ocimum bisabolenum – Kokopelli’s one, “Spice” (from Richters Seeds in Canada) and the ecotype “PI 652059” (from GRIN/USDA).

At the end of June, I sowed a few other cultivars from Kokopelli – including two strains of Ocimum tenuiflorum, of the “Krishna” type (which are normally purple, as Krishna is blue), as well as the enigmatic New Guinea Basil – which I would like to evaluate. As well as the “Anise” strain from Richters Seeds in Canada. And various batches of “Kapura”.

I then transplanted what had sprouted into small pots, and subsequently into 1 liter (or larger) pots or directly into the garden.

Some accessions, including those from USDA/GRIN, did not germinate at all.

Objectives of “Basils 2025”

I would like to clarify that the objectives of “Basils 2025” are:

1. Paying tribute to the beauty and diversity of Ocimum and photographing them more and more – just in case we ever publish a book on the main species in the Ocimum genus… about which I have already written a plethora of monographs.

Regarding the readability of my monographs – for example, those concerning the world of Ocimum – I understand that they are not accessible to everyone. As I have often said, I do not write for a predetermined audience… I write for those who can read me – quite simply. I hope that some readers will be able to summarize them more easily… for those who can read them.

The key, in truth, is to focus, to aim straight for the target – like a bee that lands on a Besobila inflorescence to savor its nectar and pollen. This is how I identify my monographs: with the “nectar and pollen” that anyone can enjoy – if they feel attracted to and desire them.

2. Conduct an agronomic assessment (amplitude, height, flower color, etc.) of all these Ocimum species and cultivars in parallel – unofficially and purely for pleasure – with the work carried out by the director of the Karlsruhe Botanical Institute, Peter Nick, in Germany: namely, the creation of a genetic map of 120 Ocimum accessions (including those from Kokopelli and GRIN that I selected) as well as the analysis of their essential oils.

For the record, I would like to mention that I became involved, in scientific and botanical exchanges, with Peter Nick – who had known the Kokopelli Association for a long time through his cycling trip to a farm in the Doubs region – when I commented on some of the conclusions of his published scientific study on the highly diverse nature of products marketed as “Indian Tulsi, Ocimum tenuiflorum” – and marketed in the United Kingdom.

I mean that no conscious British farmer would take the risk (more than once, at least!) of growing Ocimum tenuiflorum, a tropical species in his farm. I would remind that the situation is the same in North America and the rest of Europe: it is the Temperate Tulsi, Ocimum bisabolenum, that is commonly grown and marketed there, instead of the Indian Tulsi, Ocimum tenuiflorum. I have been sounding the alarm for 10 years – but to no avail among seed producers in Europe and North America… most of whom are very attached to their old refrains.

3. Produce, under mosquito nets (i.e., through strict self-pollination and without pollinating insects), pure seeds of ecotypes, cultivars or species that could potentially be introduced or regenerated.

4. Work on crosses involving the relatively mildew-resistant cultivar “Devotion” – from which I harvested a lot of seeds during the summer of 2022, when it grew among about thirty other Ocimum species and cultivars. The aim being to study dozens of plants in order to discover interesting crosses and, perhaps, also with the mildew resistance of the mother plant.

For example, I currently have 2 magnificent “Devotion x X” plants with very large purple leaves, which I am growing under a pollination tent, with mosquito net, in order to produce seeds… and perhaps even sow them in a second, more autumnal campaign, in order to scan the next generation.

It is important to note that research and breeding projects involving Basil often draw on the GRIN/USDA seed collection. For example, the recent Brazilian cultivar, “Maria Bonita” (Linalool type), comes from the Ethiopian ecotype, PI 197442 – which I grew in 2022 – whose chemotype is Linalool/Geraniol/Eucalyptol.

5. Introduce a new genetic “strain” of Ocimum bisabolenum, which is, in fact, a genetic pool from five, or more, different ecotypes. Why? Because, depending on the Ethiopian ecotypes, the ratio of Bisabolene, in the essential oil, can vary from 10 to 49%. And it is Bisabolene that interests us because this terpene is very specific to this species in the Ocimum world – at least in the spectrum of major Ocimum species from an ethnobotanical, medicinal or commercial point of view. I am also growing, in the safe pollination tent, a specimen of Ocimum bisabolenum which has very clear green leaves when the huge majority of plants, in this species, have dark green leaves.

Moreover, I am waiting for 2 seed packets, coming from USA, of the ecotype of Besobila introduced, in the 70s, by the Ethiopian Menkir Tamrat, who grew and sold Berber landraces native to his native Ethiopia in Fremont, California: basil, chili peppers, teff, etc.

In fact, as early as October 2012, [Link] a Californian newspaper, the San Francisco Gate, had revealed the Ethiopian origin of the Temperate Tulsi – but no one paid, then, any attention.

The “Temperate Tulsi” strain, of Ocimum bisabolenum, which I introduced to France, and Europe, with the first Terre de Semences organic seed-catalog, in 1994, was from the Abundant Life Seed Foundation. In 2022, I contacted its creator, Forest Shomer, who, after nearly half a century, could not remember its origin!

The current Kokopelli strain is likely that of Frank Morton in Oregon (Wild Garden Seeds), who has been growing it since the 1980s, with the Abundant Life Seed Foundation, also, as his source.

In any case, it is one of seven GRIN/USDA strains that have been circulating widely in the US since 1953: PI 652056, PI 652059, PI 414201, PI 414202, PI 414203, PI 414204, and PI 414205.

6. Mix all these basil cultivars and ecotypes in the garden to encourage Mother Earth to give us more gifts of spontaneous crosses – and, above all, “fertile” ones, because my two 2024 hybrid plants (Ocimum basilicum x Ocimum kilimandsharicum) are sterile… to date. This year, I am even going so far as to plant a “Cinnamon” or “Licorice” Basil together with an Ocimum kilimandscharicum in the same pot in order to play the lottery with the Archetype Ocimum! Why? Because it seems that my first two spontaneous crosses involved the chemotype “Methyl Cinnamate” in Ocimum basilicum.

I would like to point out that intra-specific crosses exist in Ocimum, but inter-specific crosses are very rare. This is evidenced by the inability of researchers to transfer resistance to downy mildew from various Ocimum species to market cultivars of Ocimum basilicum – all of which are highly susceptible.

7. Correct any errors in botanical species identification that persist in the Kokopelli range – as well as in the GRIN/USDA range.

Indeed, through my discovery of the geographical origin, and species nature, of the Temperate Tulsi, the Ethiopian Tulsi – which I named Ocimum bisabolenum – I was able to put an end to a botanical chaos that had been going on since 1953 in the US, when five ecotypes were introduced into the seed bank of the Tobacco Division in Ames, Iowa. These 5 ecotypes of, Ocimum bisabolenum – PI 414201, PI 414202, PI 414203, PI 414204, and PI 414205 – were specified, then, as Ocimum gratissimum and Ocimum kilimandscharicum. Link.

1953 is, symbolically, the year of my birth, and it is surely a synchronicity to the credit of the Basil Archetype!

Nevertheless, there is still enormous botanical confusion prevailing in the entire Ocimum genus (particularly among seed companies), which I have attempted to remedy, in part, with my various monographs – particularly those on Ocimum bisabolenum (in French, English, and Spanish) and Ocimum americanum.

I have, thus, highlighted that nearly a hundred studies published on Basil, over the past quarter-century, should be corrected or outright retracted. [Link] Of course, this perspective was not warmly welcomed by their authors, almost all of whom never responded to me, preferring to bury their heads in the sand. Furthermore, I do not hold a PhD conferred by the neo-Darwinist academic lottery: I am, therefore, nothing more than a peasant, and a freak, in the small world of standardized, State-certified botany and genetics.

Last year, a geneticist, from Ethiopia, whom I informed that she was not dealing, in her recent genetic study, with Ocimum basilicum but with Ocimum bisabolenum, answered me back, bluntly, that she would not read my monographs as I had never published in a reputable journal. But publishing is impossible for a peasant-scholar without a PhD! Figure it! Highly hilarious!

Today, if I may repeat myself, once again, the US seed bank (GRIN/USDA) lists seven ecotypes of Ocimum bisabolenum as Ocimum tenuiflorum – even though the flowers are purple with orange pollen according to their own photographs… and even though the high prevalence of Bisabolene, in the essential oil, is highlighted in their own observations! I have grown three of these ecotypes in my garden to demonstrate that the evidence is not just virtual on the internet: PI 652059, PI 652056, and PI 414205.

By the way, it is strictly impossible, in our garden, to see any difference, phenotypically speaking, between the diverse ecotypes of Ocimum bisabolenum: PI 652059, PI 652056, and PI 414205, “Spice” (from Richters Seeds) and the “Kokopelli” strain.

All this is corroborated by the beautiful pressed plants presented by Noelle Fuller as well as the results of her studies (LINK) – namely than “Kapoor” (misnamed by Strictly Medicinal Seeds), PI 414201, PI 414202, PI 414203, PI 414204, PI 414205, PI 652056 and PI 652059 are ecotypes of the same species, Ocimum bisabolenum. LINK. With the same level of Bisabolene, more or less, and the same predominant other elements of the chemotype: namely, Eugenol, Estragol (Methy Chavicol) and Eucalyptol.

I have just confirmed, in the Real of my garden, that reference PI 652052, supposedly Ocimum americanum according to GRIN/USDA, is in fact Ocimum kilimandscharicum – as I had indicated to the Botanical Institute of Karlsruhe based on the GRIN own pictures. Unfortunately, only one seed germinated, and I placed the only viable plant in an isolation mosquito net in order to produce seeds. Nevertheless, it is a great pleasure to encounter an ecotype of Ocimum kilimandscharicum whose chemotype differs from the common chemotype with predominant Camphor. One of the analyses of the essential oil, PI 652052, gave the following results: Estragol 31%, Camphor 12%, Eucalyptol 11%, Eugenol 9%.

It should also be noted that the ecotype of lemon Basil, originating from Esfahan, Iran, is mistakenly listed as Ocimum basilicum in the GRIN/USDA seed bank – with the reference PI 253157 – when it is actually Ocimum americanum sp. pilosum.

Similarly, the modern cultivar of lemon Basil, “Sweet Dani,” is mistakenly listed as Ocimum basilicum – with the reference PI 584458 – when it is actually Ocimum americanum sp. pilosum.

Similarly, the heirloom ecotype of lemon Basil, “Mrs Burns”, is mistakenly presented as Ocimum basilicum – with the reference PI 652054 – when it is actually Ocimum americanum sp. pilosum.

8. Attempt to establish a “botanical handbook,” with photographs, allowing the botanical species of Ocimum to be intuitively distinguished at first perception – thanks to “determining” characteristics: the color of the pollen; the height of the plant; the positioning of the plant and leaves in space; the shape of the leaves; the length of the flower stalk, etc.

For example, orange pollen characterize, specifically, Ocimum kilimandscharicum or Ocimum bisabolenum.

The color of the flowers is not a primary determining characteristic because there is great intra-specific diversity… at least among all the main aromatic and medicinal species. However, it is a secondary determining characteristic because certain cultivars, or ecotypes, of Ocimum basilicum and Ocimum americanum have flowers of a particular color.

9. Correct any errors in the botanical descriptions in my monographs on Ocimum written during the summer of 2022. In fact, in our desert-style garden, which is relatively new – and with raised beds maintained by low brick walls – and whose biomass is made from local (poor) soil, manure, and vermicompost, plant prosperity can vary greatly depending on soil fertility and location.

For example, in 2022, in my monograph on Ocimum americanum, I did not correctly describe the ecotype of Lemon Basil, “Kali,” as low-growing… because the plants reach, at least, 50 cm in height. It is clearly Ocimum americanum var. pilosum – not Ocimum americanum var. americanum as I had assumed.

So this year, I decided to grow certain plants, ecotypes, cultivars or species, of Basil that I wanted to evaluate – and photograph more easily – in 30/35 cm pots with trays, using the same growing medium and watering the plants at will.

This allows me, for example, to place the Lemon Basil cultivars “Lime Thai,” “Kali,” and “Mrs. Burns” – which are about 50/60 cm tall – side by side in order to highlight their very great similarity from a phenotypic point of view. In fact, the differences in the coloration of their leaves or flowers are subtle and would need to be validated in the field with a large number of specimens.

Only an analysis of their essential oil chemotype can truly differentiate them – if at all.

10. Establish a very precise table of the chemotypes of essential oils for each ecotype, or cultivar, of Basil presented by the Association the Kokopelli : namely, a description of their main components – as there are sometimes dozens of minor ones. This is for medicinal purposes, among others – because even Basil cultivars, known as aromatics, are extremely medicinal.

In 1986, in France, we created the “DEVA Flower Essence Laboratory” – with Sofy, my partner, and our friend Philippe Deroide – which was making, and selling, the Bach Flower Remedies and other Flowers Essences from USA. By then, Pierre Franchomme, a pioneer in essential oils, had already created his “Pranarome Laboratory.” It was this enthusiastic researcher who was the first to introduce organic essential oils with specific chemotypes, for each product, to the market. For medicinal purposes.

For example, if very similar violet cultivars – such as “Rubin,” “Osmin,” “Dark Opal,” and “Rosie” – are kept in the same range, it is then interesting to highlight their possible differences in terms of their essential components – if such differences do exist.

It is not necessarily a question of presenting precise percentages, as these can vary considerably depending on the year and the region of cultivation, i.e. depending on atmospheric conditions, cultivation conditions, harvest period, etc.

It is sufficient to present their major chemotype. For example, the ecotype of Ocimum bisabolenum, GRIN/USDA PI 652056, has the following chemotype, in order of importance: Bisabolene, Anethole, Eucalyptol, and Eugenol.

My Observations about Cultivars of Basils

My observations on certain cultivars of Basil obviously apply to a plethora of other seed producers, as the world of basil has been plagued since the middle of the last century by enormous chaos, both botanical and taxonomic, as well as in terms of identity, due to fanciful names, supposed selections, and pseudo-new cultivars.

1. Regarding the germinative capacity of Basil seeds

I mentioned in my book, “Semences de Kokopelli” – which is in its 18th edition and which has not been updated since 2011 – that the average germination period for Basil was eight years. Today, I would be much more cautious: it all depends on the species, first of all, and then on the quality of the seeds… and how they are stored.

This year, my Basil seeds from 2022 are germinating perfectly.

This year, I obtained beautiful Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants from seeds that were 8 years old – produced in 2017 – with a 91% germination rate in the July 2024 test.

“Malawi Camphor,” from 2018, has little germination capacity – with only 75% in April 2023 – but the few plants I got from it are very beautiful.

On June 28, I found Richters’s “Anis” seed-packet in my drawers and sowed the rest of the seeds – dating from 2015 or 2016 – hoping for a little germination. By July 5, hundreds of seeds had sprouted!

Furthermore, I will be even more cautious when it comes to seeds of Ocimum species from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, as reliable, sourced information on their average germination time is very rare, if not non-existent.

2. Regarding the viability of Basil seeds

For some cultivars, the seeds germinate but produce weak seedlings that do not thrive. This is an extremely important point for all seed producers: they must monitor the germination capacity of the seeds, but also their viability… because just because a seed germinates does not mean it is viable – i.e., capable of producing a robust plant. I have noticed this with various seed producers.

So, for a plant as important as Basil, it is probably wise for all seed companies to set up a mini test greenhouse in the spring. Basil is the most widely grown herb in the Western world – hence the current drama of mildew… against which organic vegetable growers can do nothing… except take preventive measures or use hi-tech fans when the few “resistant” cultivars no longer work… or are unheard of.

In principle, under identical experimental growing conditions, non-viable or very weak seedlings can be generated by seeds that are too old (and no longer have the Force, the Vital Impulse) or by seeds that have been produced in marginal conditions, given their genetic requirements (and therefore never had the Force).

For example, I had weak plants with “Mrihani” (2017), “Kivumbasi Lime” (2018), ”Vana“ (2020), “Rama” (2020), etc., and this is likely due to the age of the seeds.

But I also had some stunted plants with “Green Tulsi from Thailand,” which is from 2022 – while another Ocimum tenuiflorum, from Gujarat (GRIN/PI 288779), was normally developed and three times larger for the same sowing date. Similarly, a basil known as “African,” from 2022, produced seedlings that remained 1 cm tall. This lack of viability may be due to a lack of heat at the seed production site.

Today, given atmospheric fluctuations – including cooling trends – it is more than prudent to produce Ocimum tenuiflorum and Ocimum gratissimum seeds in greenhouses… or in the warmest regions of France or Europe.

3. The first plants of Basil to flower, on May 28, were Ocimum bisabolenum

They were followed a week later by small-leaved lemon basil. The first plants to produce ripe seed, around June 20, were Ocimum bisabolenum.

4. Regarding Cristation/fasciation in Ocimum bisabolenum

I have discovered a new characteristic that is unique to Ocimum bisabolenum… at least as far as I know – which is to say, a lot! – about the main species of Basil in the world. Indeed, some plants, from various ecotypes of Ocimum bisabolenum, have a stem characterized by a cristation/fasciation that can reach 5 cm in length – with a width of nearly 9 mm. Then, this main stem, in fasciation, divides into two or three branches.

5. Regarding the cultivars of the species Ocimum basilicum – namely the most widely used, cultivated, and marketed

As a reminder: cultivars with a high linalool ratio constitute the largest share of the market for Basil used in food. For example, depending on the analyses and growing conditions, the cultivars “Greco a Palla” and “Genovese” can contain up to 75% linalool.

Caveat: these two names, and many others, can often refer to different ecotypes, selections, etc., with different chemotypes. For example, a 2004 study found that “Greco a Palla” had a chemotype of 30% eugenol and 24% linalool. [17] For example, some “Genovese” may contain high levels of estragole.

Regarding the purple-leaved cultivars “Rubin,” “Osmin,” “Rosie,” and “Purple Delight,” I see no difference, this year, between these four cultivars in terms of coloration.

Nevertheless, an ad hoc plot with numerous specimens would need to be cultivated in order to assess the permanence of the purple coloration throughout the season and, above all, its resistance to high temperatures. In hot environments with very little watering, it is clear that all cultivars of purple basil revert to green coloration… or wither very quickly.

I was unable to evaluate the “Dark Opal” cultivar in comparison, but according to the photos on the Kokopelli website, it appears to be almost identical.

I have grown the Richters Seeds cultivar “Purple Delight” several times and have seen no difference in coloration compared to the others.

In fact, there is a plethora of purple, red-violet, and violet basil culitvars on the seed market, with various names—both controlled and uncontrolled: “Purple,” “Red Genovese,” “Grenat,” “Prospera Rouge,” “Rosalie,” “Purple Petra,” “Amethyst,” “Purple Ball,” “Deep Purple,” etc., etc.

The main antioxidant compounds, in purple Basil, are the acids caffeic, vanillic, and rosmarinic, as well as quercetin, rutin, apigenin, chlorogenic acid, and p-hydroxybenzoic acid.

The main components of the chemotype, of purple Basil, are: eucalyptol, linalool, estragole, eugenol, methyl cinnamate, and trans-α-bergamotene.

The chemotype of the essential oil of the two cultivars, “Rubin” and “Osmin,” is very similar, with approximately 60 to 65% linalool, which is very predominant. These two cultivars differ in terms of the presence of other components: eucalyptol, eugenol, bergamotene, germacrene, and bourbonene.

According to a 2017 analysis [10], Rubin contained 71% eugenol. According to a recent 2025 study [14] , the chemotype was estragole, linalool, eucalyptol, and α-pinene.

As for “Dark Opal,” its chemotype, according to a 2012 analysis, contained approximately 40% linalool with 20% bergamotene and 6% eucalyptol. Another study from 2004 attributed a chemotype of linalool (55%) and eucalyptol (18%) to it. [17] Another study, from 2003, attributed a chemotype of linalool, estragole, and eucalyptol to it.

The same analysis, conducted in 2012, characterized “Purple Ruffles” – another purple cultivar resulting from a cross between “Dark Opal” and “Green Ruffles” – as having 32% linalool, 16% estragole, 10% eucalyptol, and 10% bergamotene. Another Brazilian study, from 2004, attributed a cinnamon chemotype (methyl cinnamate and linalool) to this cultivars. Another study, from 2004, attributed a 55% estragole chemotype to it, followed by linalool (19%) and eucalyptol (11%).

As for the purple basil from the Arapgir region of Turkey, renowned as the basis for a purple cheese pesto, its chemotype is methyl cinnamate (approximately 45%), linalool, and eucalyptol, according to a 2022 study that examined the levels of these components based on the quality of agricultural soils. [9] Arapgir’s purple pesto is therefore a cinnamon pesto.

Regarding cultivars such as Linalol, Grand Vert, A Feuilles Moyennes, Dolly, Elidia, Eleonora, etc. They are of no interest, especially since some may have been resistant to mildew, in the past, but are no longer so today.

A traditional cultivar, such as “Genovese”, is more than sufficient for culinary Basil of the Linalool type with medium-sized leaves – but, caution, it has no resistance to mildew.

Regarding the “Latino/Vert Fin Compact” cultivar. It seems completely similar to the “Grec” cultivar but without its incredible growth – at least in my garden. The “Grec” cultivar is, sometimes called, “Greco a Palla.”

There is a “Vert Fin” type ecotype, but not compact – and of the Linalool/Geraniol chemotype – originating from Çanakkale in Turkey.

Regarding the cultivars “Siam Queen Thai,” “Small-leaved Thai,” and “Red-stemmed Thai. I really don’t see any difference between these cultivars – except for slight differences in flower color – with a similar chemotype, at least to the nose. I was unable to evaluate “Large-Leaf Thai” as it was sold out at Kokopelli. In fact, “Small-Leaf Thai” has “large” leaves measuring 6/7 cm… at least according to my own leaf meter.

I am also awaiting the results of analyses of their essential oil and their “genetic map.” A 2012 study of “Siam Queen” gave 84% estragole and 4.5% bergamotene.

Regarding the cultivars “Anise,” “Licorice,” “Cinnamon,” and “Aromatto.” I need to investigate all these cultivars… especially since my erroneous attribution of Ocimum americanum for “Anis”, from the Kokopelli range, was extrapolated from a strain from the seed company Richters Seeds – which I grew in 2022.

On June 28, I found the Richters “Anise” packet in my drawers and sowed the remaining seeds – dating from 2015 or 2016 – hoping for some germination. By July 5, hundreds of seeds had sprouted!

From a phenotypic point of view, there is no real difference between the “Anise” “Licorice” and “Cinnamon” cultivars from Kokopelli, and sometimes very little difference with certain “Thai” ecotypes as well, due to the fact that they all belong to the same “Thyrsiflorum” group.

In fact, according to a recent study from 2023, the cultivars “Anise” “Licorice” and “Fahéj illatú” (“Cinnamon aroma” in Turkish) all have a Cinnamon/ Linalool chemotype – with more than 50% methyl cinnamate for the “Licorice” cultivar. The ”Anise” cultivar has less methyl cinnamate but much more estragole (25%).

In the Kokopelli range, the “Aromatto” cultivar is also a “Cinnamon” chemotype.

What’s more, there are at least three types of basil called “Anis” on the internet, depending on the seed producer. The first is the “Anis” type currently sold by Kokopelli. The second is the “Queen of Sheba” type, supposedly a new introduction by the Dutch company Sahin in 2001, which is clearly an ecotype from Eritrea and Ethiopia – such as PI 197442, known as “Ajuban“ or “Ashkuti.” A third cultivar is an ecotype of Ocimum americanum, as there are ecotypes of this species, for example in India, with nearly 80% methyl cinnamate in their essential oil. A fourth cultivar was analyzed in 2019 and found to contain 81% estragole and 8% eucalyptol.

As for the Richters Seeds cultivar, it has elongated, thick leaves with purple veins and very purple flowers—according to my photos from 2022.

According to a 2019 study, a cultivar called “Anis” had a chemotype of “Estragol” (81%) and Eucalyptol (8%). [17]

It is clear that using the same names for completely different ecotypes only exacerbates the botanical confusion surrounding basil plants that has existed for decades. The same is true of the multiple – and often fanciful – names given to a single ecotype or cultivar.

There is a plethora of other cultivars – or trade names, to be more precise – of Basil of the “cinnamon/methyl cinnamate” type: “Purple Virgin,” “Purple Lovingly,” “Sweet Castle,” “Purple Long Legged,” etc.

6. Regarding companion planting involving Tomatoes and Basil in the vegetable garden.

I scattered Basil throughout our large garden this year – including among the tomatoes. My conclusion at the end of June is as follows. In a relatively arid biotope such as ours (in 2024, 95 mm of water between early January and late September), a very low water table at a depth of 125 meters, and many days already reaching 92°F in June, the tomato/basil companion planting is, inevitably, beneficial to the tomatoes – in terms of harmonizing insects – because the Tomato plants literally “suck” up the water… and then the light.

It is easy to imagine that, from the point of view of biomass production, there is no possible competition between Basil and Tomatoes – the latest being very demanding in terms of nutrients. Indeed, the root system of Tomatoes monopolizes water and, subsequently, their canopy blocks out light, preventing Basil from developing harmoniously.

Opposite, a photo of a stunted Mammoth plant, 20 cm tall, with very small leaves, between two tomatoes. Below, a photo of a normally developed Mammoth plant in a pot, with leaves 20 cm long, including a 3 cm petiole.

Traditionally – and we practiced this, extensively, since 1993 with the Jardin Botanique de la Mhotte in Allier – Marigolds are part of this Tomato/Basil companionship. In our garden, we have no shortage of them, as we are constantly invaded by nematocidal marigolds (Tagetes minuta) – which have a particularly robust root system – that we have to control.

7. Regarding temperatures exceeding 35°C/105°F.

In front of our cabin, none of my Basil plants, which are in large pots, suffer from the intense sunlight and high temperatures. Why? Because they have unlimited water in their containers. The situation is different in the garden, with plants growing in the ground… Thus, under the same conditions, and depending on the cultivars, or ecotypes, some plants – such as those of the violet type – wrinkle their leaves as much as possible or let them hang down, while others have not initiated any foliar process to minimize evaporation.

For now, I have noted the following cultivars of Ocimum basilicum as being highly resistant to heat: “Greek”, “Queen of Sheba”, “Napoletano”, “Mammoth”, “Lettuce”, “Obsession”, “White Spires” – as well as the purple cultivar currently being selected, “Opalescent”… perhaps due to its genetics from the tropical ecotype, “Mrihani”, from Zanzibar.

As for the species Ocimum tenuiflorum, Ocimum gratissimum, Ocimum campechianum, Ocimum selloi/carnosum, and Ocimum kilimandscharicum, their ecotypes, due to their geographical origins, are all naturally very resistant to heat – as are certain ecotypes of Ocimum americanum such as “Malawi Camphor” and “Kivumbasi Lime.”

As for the species Ocimum bisabolenum, it is not very resistant to heat, being temperate by nature, as it originates from the high plateaus of Ethiopia – up to 2,800 meters above sea level. Therefore, when the temperature reaches 40°C in the shade, it folds its leaves in the sun.

8. Regarding ecotypes, and cultivars, of Ocimum americanum

As for the Lemon type Basils, “Lime Thai,” “Kali,” and “Mrs Burns,” when placed side by side, they are characterized by a very high degree of similarity from a phenotypic point of view. They were approximately 50 to 60 cm tall at the end of June.

The differences in the coloration of their leaves or flowers are subtle – a brighter green and a hint of mauve in the flower heads of “Mrs. Burns” – and, moreover, would need to be validated in the field with a large number of specimens. “Mrs Burns” is said to reach 90 cm in height in the 1996 book “Basil” by DeBaggio and Belsinger.

As I have already mentioned, plants of the “Kali” ecotype, in addition to their 60 cm height, currently have medium-sized flowers. It is therefore clearly Ocimum americanum var. pilosum – and not Ocimum americanum var. americanum as I had assumed – especially since this lemon Basil is strictly native to India and Southeast Asia.

It is therefore, only, the chemotype of their essential oil that can differentiate these various cultivars of Ocimum americanum var. pilosum:

I have not found any information on the chemotype of the “Kali” ecotype – awaiting analysis. Moreover, this Ocimum americanum var. pilosum is rarely presented as such on the Internet. Most Lemon Basil ecotypes, in the USA, date back to the introduction of Thai strains by the US Department of Agriculture around 1940 – sometimes marketed under the name “Maenglak Thai.”

“Sweet Dani.” The chemotype of its essential oil is 83–86% citral. In addition, this recent v has a higher essential oil ratio than other cultivars of lemon basil, meaning it contains even more citral.

“Mrs Burns”. The chemotype of its essential oil is Estragol, Citral, and Linalool, with even traces of Bisabolene according to one study. According to another study, it is 50% Citral and 39% Linalool – without Estragol. [17]

This ecotype was cultivated by Mrs Clifton, from New Mexico, since the 1920s. It was introduced commercially by one of the administrators of the Native Seeds Search network in Arizona. Lemon basil is very common in western China and most likely arrived in the US in the 19th century with Chinese workers during the westward railroad boom.

“Lime Thai” – ou “Maenglak Thai”. The chemotype of its essential oil is Citral, β-Caryophyllene, Linalool, and Bergamotene.

As for the Lemon Basil ecotype native to Esfahan, Iran – a place recently highlighted by the bombing of its nuclear research site – it is a lemon-scented Ocimum americanum var. pilosum with very large plants. The main chemotype of its essential oil is Citral, Estragol, Linalool, and Bergamotene.

This Iranian ecotype is even more developed in terms of biomass than the “Mrs Burns,” “Kali,” and “Lime Thai” cultivars: at the end of June, plants of this “Esfahan” ecotype are already 80 cm tall. It is magnificent because it has white flowers with two phenotypes: one with purplish flowering tops (due to the purple color of the calyxes) and the other with non-purplish flowering tops.

It should be noted that it is mistakenly listed as Ocimum basilicum in the GRIN/USDA seed bank, with the reference PI 253157.

Regarding the subspecies, Ocimum americanum var. americanum. First, concerning the ecotype “Kivumbasi Lime”, originating from the island of Zanzibar. Having never cultivated it myself, I attributed it to Ocimum americanum var. pilosum. This was a mistake on my part: it is an Ocimum americanum var. americanum.

Next, regarding the “Genetic Pool from Zambia” from Kokopelli. I already have two magnificent plants, in isolation mosquito netting, and I just reseeded a tray – and transplanted about ten seedlings – from a whole packet of old seeds. Indeed, I wish to locate the plants – from this genetic pool of four Zambian ecotypes – that possess an Eucalyptol chemotype rather than a Camphor chemotype. For medicinal purposes.

Indeed, an Eucalyptol chemotype of Ocimum americanum var. americanum would expand the range of Kokopelli for this subspecies: in addition to “Kivumbasi Lime”, with a Citral chemotype, and “Malawi Camphor”, with a Camphor chemotype – and perhaps, to be verified, a Menthol chemotype, for the reference named “African”, without a more precise geographical origin.

Regarding ecotypes of Ocimum tenuiflorum

Regarding the “Green Tulsi from Thailand”. It started to bloom, at 25 cm in height, at the end of June. Note that its leaves are slightly different from other ecotypes of Ocimum tenuiflorum, as their curling suggests that they are not serrated at all… whereas they are.

I have not obtained anything from the seeds from 2020 of the ecotype named “Rama”.

At the end of June, I sowed two purple strains of “Krishna” – which germinated very well – in order to assess what the issue was regarding their coloration. In fact, both of them are misidentified as they are green-leaved.

I found the photographs taken by our daughter Laetitia, of our experimental Basil crops, in Costa Rica, during the summer of 2017: indeed, there was a “Krishna” ecotype with red stems but completely green leaves. But, then, there was, also, in the Kokopelli range, a real “Krishna” with red leaves – as I grew it twice, myself, in Costa-Rica and Oregon in 2017 and 2018.

By the way. Noelle Fuller informed me, recently, of the issue, in USA, concerning the availability of seeds of real purple Krishna ecotypes of Ocimum tenuiflorum.

I positioned, in my isolation mosquito tents – in order to produce pure seeds – plants from two other ecotypes, green, of Ocimum tenuiflorum: one from Gujarat (PI 288779) and the other from Cuba (PI 652057).

The Tulsi from Gujarat has an Eugenol, Elemental, and Caryophyllene chemotype – according to a very old analysis of its essential oil. As for the Tulsi from Cuba, it has a β-Caryophyllene chemotype.

Regarding the spontaneous crosses involving “Kapura”, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, and Ocimum basilicum

This year, I sowed “Kapura” seeds stemming from my very diversified Basil garden from 2022, as well as seeds from a plant that appeared spontaneously during the summer of 2024, along with seeds produced by Maryse, one of Kokopelli’s growers in 2017.

In India, Ocimum kilimandscharicum got its name “Kāpūra” from the term for “Camphor” in Marathi. But nothing is simple in this gigantic country. “Kapura” is also the term for the species Camphora officinarum in Kannada and Marathi; as well as the term for Limnophila indica in Odia; and also the term for the species Cinnamomum camphora and Ehretia laevis – in India.

Moreover, among the Tantric Pagans of Shaktism in India, Kāpura is one of the 16 Siddhas, one of the 16 “Instructors” – and “Liberators”…

I have about twenty “Kapura” currently growing, in pots or in the garden. And I have already discovered several “abnormal” plants with different flowers and leaves – which all seem sterile at first glance.

For example, four of these abnormal “Kapura”, seemingly less camphor-like, have flowers with relatively short stamens and anthers that are white/gray completely devoid of pollen – instead of orange anthers, with orange pollen, and very long stamens.

Three of these plants are huge and three are characterized by hyper-branching: the main stems produce 12 to 24 floral spikes measuring 6 to 10 cm long.

As for the other abnormal “Kapura”, their young leaves are very wrinkled and their flowers have a slightly mauve coloration – with orange pollen.

It should be noted, above all, that the species Ocimum kilimandscharicum is very uncommon in gardens and very little investigated by researchers… because research is expensive. For example, a query on the Pubmed website presents 1500 references for Ocimum basilicum, 847 for Ocimum tenuiflorum, and 47 for Ocimum kilimandscharicum! This indicates that the reproductive processes characterizing Ocimum kilimandscharicum have not, really, been elucidated.

Thus, it seems established that Ocimum kilimandscharicum can cross spontaneously, and often… unless Mother Earth has decided, spontaneously, to bestow upon me recurring botanical gifts!

After inquiring into the past seed productions of Kokopelli, I also suspect that these new hybridized plants of Ocimum kilimandscharicum may have originated from a spontaneous cross during the 2017 season, at Maryse’s, who produced 337 grams of seeds as well as nearly a kilo of the ecotype Ocimum basilicum, ‘Mrihani’ – namely, a significant opportunity for crossings, involving these two species, due to the very large number of seed-bearing plants… and the irresistible attraction of pollinators from all spheres.

This proximity, at Maryse’s seed production farm, between “Mrihani” and Kokopelli’s camphor ecotype of Ocimum kilimandscharicum – which may be fatal in terms of seed purity – that I have just discovered, in a seed database, is a very fascinating synchronicity!

Indeed, not long ago, I discussed with the director of the Botanical Institute of Karlsruhe, Peter Nick, the hypothesis that an ecotype from East Africa, the Kilimanjaro Basil, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, may have crossed with the local ecotype of Zanzibar of Ocimum basilicum – referred to as “Mrihani”… from the Arabic term “Reihan“ for Basil. This spontaneous cross might be the source of its complete, and unique in the world, resistance to Basil Downy Mildew.

This hypothesis is interesting insofar as Zanzibar is located, in the Indian Ocean, almost directly opposite Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Moreover, coincidentally, the Basil downy mildew, Peronospora belbahrii, is also native to the area of Tanzania and Uganda – in 1932.

Some geneticists refer to plant immune receptors – the leucine-rich repeat proteins NLR – or multifunctional receptor-like kinases to explain this exceptional resistance to Peronospora belbahrii… but this, in no way, indicates the source of the genetic transfer or the evolutionary emergence.

In conclusion, in terms of the integration of genes for resistance to Basil Downy Mildew, into edible Basil cultivars of Ocimum basilicum, the Ocimum kilimandscharicum X Ocimum basilicum pathway could prove fruitful. This is especially true if less “camphoraceous” ecotypes of Ocimum kilimandscharicum are available, as consumers are not fond of camphor on their plates. There are, in Africa, for example, other ecotypes of which are devoid of, or very low in, Camphor. Such is the case for the GRIN/USDA ecotype, PI 652052, which had for chemotype, in one analysis: Estragol 31%, Camphor 12%, Eucalyptol 11%, Eugenol 9%.

Clearly, Ocimum kilimandscharicum loves to flirt! And given my first spontaneous cross involving Ocimum basilicum x Ocimum kilimandscharicum, producing branches with white flowers and branches with purple flowers, it is certain that this species behaves playfully – considering the standardized and official claims. Who has heard of Basil plants with tho kind of flowers?

In conclusion, if Ocimum kilimandscharicum spontaneously crosses with Ocimum basilicum, and vice versa, it is quite possible that Ocimum kilimandscharicum could cross with other species of Ocimum, and vice versa – at least among the Ocimum species of the clade comprising Ocimum basilicum, Ocimum americanum, Ocimum kilimandscharicum and Ocimum bisabolenum.

It is certain that seeds of Ocimum kilimandscharicum must be produced away from any cultivar of Ocimum basilicum – and, for caution’s sake, away from any other species of Ocimum.…

… and away from bees carrying, possibly, pollen from Basil from the surrounding gardens… because bees (domestic and wild) as well as bumblebees love and indulge in the royal pollen of Basil. And, sometimes, they come from very far away for Basil pollen and nectar… as their quest is for the Best.

In this regard, my various letters, from the autumn of 2024, addressed to ITEIPMAI and its director, Denis Bellenot, have to this day remained unanswered. I narrated my discoveries and even proposed cuttings of my spontaneous crosses… in the name of Research and Mutualism.

Maybe the researchers at ITEIPMAI are angry? It’s true that in my 2017 essay, “Tulsis and other Basilico-molecular Truths to Free Yourself from Pharmacratic Terror,” I had somewhat ironized about the fact that “the researchers of the Milarom project, from ITEIPMAI, discovered 12 sources of gene resistance to basil downy mildew but they did not know where these sources come from because all the original experimental cultivations were carried out in open pollination.”

In my various letters, I even proposed to this administrator of the “National Conservatory of Perfumed, Medicinal, Aromatic and Industrial Plants” in Milly la Forêt, the friendly use of my high-definition photographs for a future edition of their excellent 286-page work, “La diversité du genre Ocimum dans les collections du CNPMAI”.

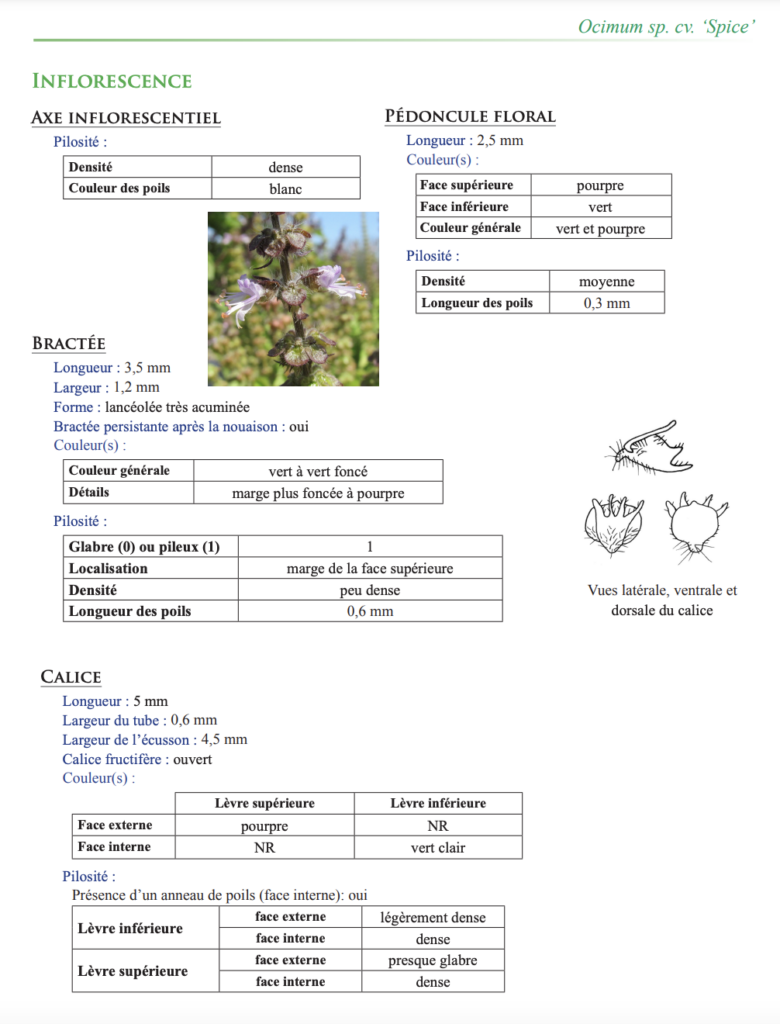

Moreover, in this very detailed document, the Conservatory of Milly la Forêt presents the ecotype of Ocimum bisabolenum – known as “Spice” or “Blue Spice” – with its orange anthers and a rigorously accurate image. Just with the illustration of the calyx, it is clear that Ocimum bisabolenum is a fully-fledged species.

With this joyful news – regarding innovation and spontaneous co-evolution – involving Ocimum kilimandscharicum, I will conclude this “First Report” on my “Basils 2025” project… hoping, one day under a lucky star, that the Ethiopian Tulsi, the Besobila, Ocimum bisabolenum, may also fall in love with flirting in order to spread its Bisabolene, and its resistance to cold temperatures and Downy Mildew, in the Biosphere of Basil Master Medicinal Plants!

“Yanmoole sarva tirthaani yannagre sarva Devata Yanmadhye sarva Vedascha Tulasi taam Namamyaham”.

I bow down to the Tulasi, at whose base, the roots, are all the holy places, at whose top reside all the divinities, and in whose middle are all the Teachings, the Vedas.

Xochi. July 12nd 2025