Summary

How to distinguish the various main species of Ocimum at first glance… or at first sniff?

Photographs of Leaves and Fruiting Calyxes of the various main species of Ocimum

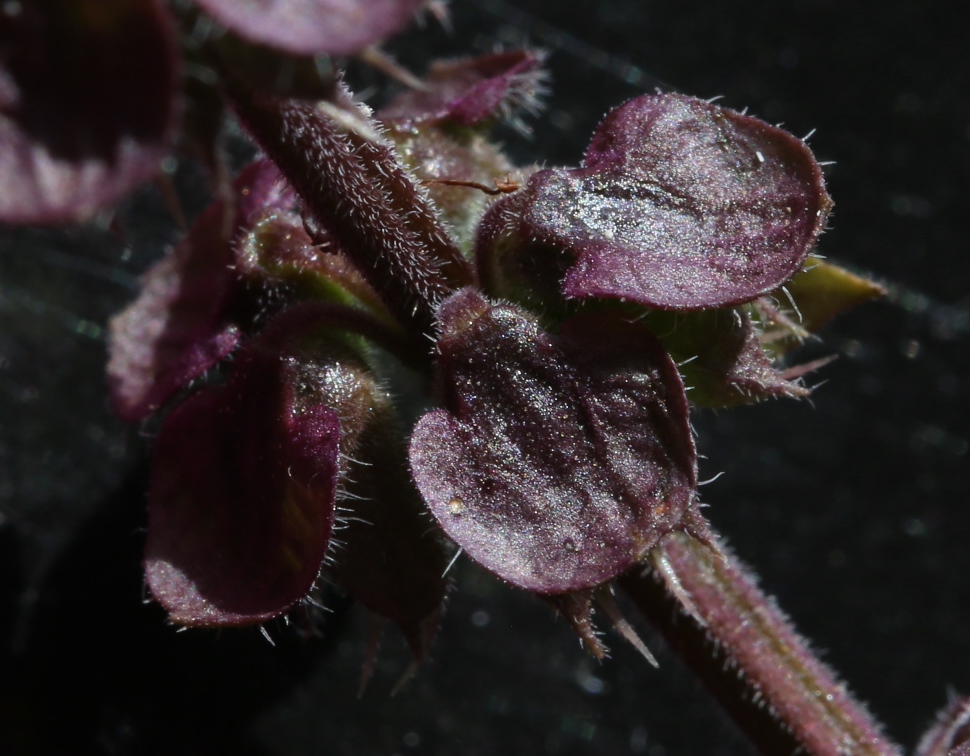

Ocimum americanum var. pilosum

Ocimum americanum var. americanum

Foreword

That being said, and presented photographically, below, any human being who genuinely cultivates an intimate connection with species of Basil, of the genus Ocimum, will recognize them “at first sight” – that is, at the mutual rebirth of this connection.

This mutual connection is established, once again, in a holistic manner—that is, with the plant perceived in its entirety: its habit, its flowers, its pollen, its leaves, its bracts, its calyxes. etc.

Thus, all the main species of Ocimum, presented below, can be recognized “at first glance,” with the occasional exception of certain ecotypes of Ocimum americanum var. pilosum… which can, nevertheless, be recognized “at first touch” – that is, at the first whiff of Citral when their leaves, or flower tops, are gently touched.

It should, also, be noted that certain ecotypes of the “purpurascens” type, of Ocimum americanum var. pilosum, with chemotypes other than Citral predominating, are difficult to differentiate from Ocimum basilicum at first glance. These include, for example, the ecotypes “Anis” (Richters Seeds. Canada) and “Nouvelle Guinée” (Kokopelli). This is why many studies continue to present them as such, even though geneticists have formally placed them in the same genetic clade as Ocimum americanum var. pilosum.

In fact, if I may digress into somewhat philosophical considerations, Basil species are like the Peoples of the Earth. The Ocimum genus is an “Archetype,” but it is not manifested in physical reality: it only has an informational (genetic) reality.

And if I may digress a little further, “philosophy” is understood in the etymological sense of “the Love of Wisdom” but also “the Love of Sophia,” the Mother. The Anthropos, like the Ocimum genus, is the fruit of Sophia’s living Biosphere, which has granted her beloved child the privilege of contemplating, investigating… and using all the other fruits of her Earthly Biosphere.

It is the diverse species of the genus Ocimum – Ocimum basilicum, Ocimum bisabolenum, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, Ocimum tenuiflorum, Ocimum gratissimum, etc. etc – that constitute the manifestations, the “Chlorophyll sub-Archetypes,” in the physical reality, of this Ocimum Archetype. Furthermore, these species, as physical manifestations of the Ocimum Archetype, originate from a specific Biotope: they are, literally, shaped by their environment.

They are authentically orchestrated by the Terroir, the part of the Living Biosphere from which they emerge, from which they emanate – whether small or large, on the scale of a region, a country, a subcontinent…

The same applies to the Peoples of the Earth. Humanity (with a capital H) does not exist: it is merely an inept concept born of a nebulous ideology that seeks to globalize human beings into a universal melting pot. Hence the existence, for example, of the UN, the Organization for Universal Leveling – sometimes in “Gaza” mode… but not always.

It is the Anthropos that exists, as an informational and genetic Archetype. And it is the Peoples, the Ethnos, the Tribes, of the Earth, that are the physical manifestations – the “sub-Archetypes in Flesh and Blood” – of this Anthropos. Just like the various species of Basils, the various Peoples, Ethnos, and Tribes of the Earth originate from a specific Biotope: they are, literally, shaped by their environment.

The Peoples, Ethnos and Tribes of the Earth are authentically shaped by the Terroir, the part of the Living Biosphere from which they emerge and from which they emanate – with their own language, culture, mortuary practices, food and medicinal plants, rituals, culinary practices, songs, hunting, and stalking.

The aim of this essay – currently under investigation and photography – is to present a morphological guide to distinguish the various main species of Ocimum: Ocimum bisabolenum, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, Ocimum tenuiflorum, Ocimum gratissimum, Ocimum basilicum, Ocimum americanum, Ocimum carnosum/selloi et Ocimum campechianum.

This is achieved with the help of numerous photographs taken with a 100 mm Canon macro lens, which obviously has its limitations, as it is sometimes difficult for me to obtain a good photographic definition with floral organs measuring 3 to 6 mm. That being said, I am nevertheless very pleased to be able to present photographs in which the pollen grains, which are white or brick red in color, and approximately 50 microns in diameter, are clearly visible!

How to distinguish the various main species of Ocimum at first glance… or at first sniff?

Sometimes, if you are sensitive, the distinction can be made at first sniff, based on the predominant chemotype – but nevertheless in synergy with a holistic view of the plant. Thus, a low plant with a bluish aura, and a Myrrh scent, is Ocimum bisabolenum. A very tall plant with a Camphor scent is Ocimum kilimandscharicum. A fairly low plant with slender leaves, and a Camphor scent, is Ocimum americanum var. americanum. A fairly tall plant with a Lemon scent is Ocimum americanum var. pilosum.

How can you distinguish between the various main species of Ocimum at first glance? First and foremost, by the color of the pollen on their mature stamens, as well as the color of the anthers. Next, by the color of the flowers, the overall appearance of the plant, and the shape of the leaves, bracts, and calyxes.

Orange/brick red Pollen:

Ocimum bisabolenum. Secondly, this species is easily characterized by the mauve color of its entire flower, its very low and highly structured habit, and its very intense fragrance of myrrh, vanilla, and tutti-frutti.

In Ocimum bisabolenum and Ocimum kilimandscharicum, the anthers are also orange in color.

Ocimum kilimandscharicum. Secondly, this species is easily characterized by the white color of its flowers, its long stamens, its very unstructured habit – and, for most ecotypes distributed in the Western world, by a chemotype strongly predominant in Camphor.

Both are very hardy species that can withstand temperatures as low as 14°F ( -7°C) during the winter.

Yellow Pollen:

Ocimum tenuiflorum. Secondly, this species is easily characterized by the pinkish-purple color and the long peduncle of its flowers, by its very loose habit and by the very crinkled shape of its leaves.

In Ocimum tenuiflorum and Ocimum gratissimum, the anthers are also yellow in color.

Ocimum gratissimum. Secondly, this species is easily characterized by the green-yellow-brown color of its flowers, by its very broad leaves, and by its very tall, upright plants.

Both species require a lot of heat, and in certain regions, it is advisable to grow them in a greenhouse.

White Pollen:

Ocimum basilicum. Specifically, some cultivars, but not all, are easily characterized by the crinkled and ruffled shape of their leaves. (“Mammoth”, “Napoletano” et “Laitue”); by the very purple color of their leaves (“Purple Rubin”, “Osmin”, “Rosie”, “Purple Ruffles”, etc); by the globular shape of their plants (“Grec”, “Floral White Spires”); by very small leaves (“Grec”, “Latino”); by floral clusters with very dense cymes (“Cardinal”, “Magical Michael”).

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between Ocimum basilicum and Ocimum americanum. Using a macro lens, it is possible to see that their calyxes are quite different.

Ocimum americanum. Specifically, some cultivars, but not all, are easily characterized by the small size of their flowers in Ocimum americanum var. americanum; by a chemotype predominantly containing Citral in Ocimum americanum var. pilosum; by a chemotype predominantly containing Camphor in Ocimum americanum var. americanum.

In Ocimum basilicum and Ocimum americanum, the anthers are also white or creamy white in color.

Ocimum carnosum/selloi. Secondly, this species is easily characterized by the shape of its flowers – in particular, the calyx – by the shape of its leaves, by the brown color of its anthers… and by its overall appearance.

Ocimum campechianum. Secondly, this species is easily characterized by the difficulty of seeing its tiny flower in the center of the calyx, by the reddish color of its anthers, by the shape of its leaves, by the shape of its calyxes… and by its overall appearance.

How can Ocimum bisabolenum and Ocimum americanum be distinguished specifically by the morphology of their flower stems?

Caveat. The purpose of this section is to highlight, based on the morphology of their respective flower stems, that there is no possibility of asserting, as some botanists still do, that the temperate Tulsi, the Ethiopian Besobila – which I have named Ocimum bisabolenum – could be Ocimum americanum… and even less so Ocimum americanum var. pilosum.

This is in addition to characteristics specific to Ocimum bisabolenum, namely: orange pollen and anthers; entirely mauve flowers; a scent of myrrh, vanilla, and tutti frutti; and a very low, highly structured growth habit.

For example, the pollen grains of of Ocimum bisabolenum are 40% octacolpate, 30% heptacolpate, and 30% hexacolpate. In contrast, those of Ocimum americanum are 87% hexacolpate.

As for those of the “cinnamon” type, from Ocimum basilicum, they are 100% hexacolpate. LINK

For example. The weight of 1,000 seeds of Ocimum americanum var. pilosum is approximately 1.7 g/2 g, while it is only 0.5/0.6 g for Ocimum bisabolenum. As for Ocimum americanum var. americanum, it is approximately 0.6 to 0.7 g per 1,000 seeds.

Furthermore, the closer photographs, presented in the following section, clearly highlight that the shape of Ocimum bisabolenum seeds is, strictly, different from that of Ocimum americanum var. americanum – although their size is almost similar.

For example, with regard to the hairiness of the calyx. In Ocimum bisabolenum, the upper lip (the calyx shield) is almost hairless on the outer surface, and the lower lip is densely hairy on the inner surface.

In Ocimum americanum var. pilosum, the upper lip (the calyx shield) is hairy on the outer surface and the lower lip is hairless on the inner surface.

These are two other characteristics of the calyx that distinguish the two species.

Ocimum bisabolenum grows to an average height of 35 to 40 cm in the garden. However, it can easily reach 55 cm in width, especially since this species of Ocimum is very adept at occupying all the space available to it. In a well-watered pot, the plants can reach 50 cm in height but, above all, spread very generously downward.

The flower stems are, on average, 10 to 12 cm long and can reach up to 18 cm. As for the dry calyxes, the largest are about 4 mm wide.

There is no diversity in terms of shape, color of flowers, or pollen in the various ecotypes of Ocimum bisabolenum that have been commercially available since 1955 – at least, those that I am familiar with. The only variation I have noticed, to date, concerns the color of their leaves: some plants are a much lighter shade of green.

I am still searching for white pollen in Ocimum bisabolenum, according to Paulos Cornelis Maria Jansen’s 1981 book, “Spices, condiments and medicinal plants in Ethiopia, their taxonomy and agricultural significance.”

So, in September, I replanted around fifty seedlings from Ocimum bisabolenum seeds sold by Bene Seeds in the USA. This ecotype was introduced, to California, in 1971, by Menkir Tamrat, an Ethiopian who was then working at IBM. It has nothing to do with the seven GRIN/USDA ecotypes distributed in the US, since 1955, which are still presented today as Ocimum tenuiflorum.

I would like to verify whether the ecotype transmitted by Menkir Tamrat has, exceptionally, white pollen, as it appears to have in a 2014 photograph in the Californian newspaper San Francisco Gate, which featured the Ethiopian gardens of Menkir Tamrat – who had left IBM. In fact, two years before I raised the alarm about the botanical chaos surrounding this unknown species, the San Francisco Gate had very clearly offered the solution to the enigma by presenting a photograph with the captions “Holy Basil” and “Ethiopian Besobila.”

The interval between the “cymes” (6 flowers simulating a whorl around the stem) is very small. Thus, there are 21 cymes on an 18 cm floral stem – i.e. with an average interval of 8.5 mm.

There are thus twice as many cymes in Ocimum bisabolenum as in Ocimum americanum var. pilosum – for the same length of flower stalk.

When dry, the largest calyxes are 4 mm wide, while those of Ocimum americanum var. pilosum are 5.5 mm wide and those of Ocimum americanum var. americanum are 3 mm wide.

Ocimum americanum var. pilosum – namely the different ecotypes that I have grown this year – are, on average, approximately 50 to 85 cm tall in the garden.

These are the following ecotypes: “Kali”, “Mrs. Burns”, “Sweet Dani”, Lime Thai”, “Anis” (Richters Seeds), “Nouvelle Guinée” (Kokopelli) and the Turkish ecotype of Lemon Basil, “Esfahan, PI 253157”.

The flower stems are, on average, 20 to 30 cm long in “Sweet Dani” and 17 to 30 cm long in “Esfahan. PI 253157.” As for the dry calyxes, the largest are approximately 5.5 mm wide.

I recall that this year, the tallest Basil stems I measured, in the garden, were 36 cm long in “Esfahan.” This record was broken, on the balcony, by a crossed Ocimum kilimandscharicum, Kapura X. SP. 01/2025, which grew to a length of 38 cm.

The interval between the “cymes” (6 flowers simulating a whorl around the stem) is relatively large. In Lemon-type Basil, the interval between cymes depends on the variety and ecotype: it varies from 16 mm to 19 mm.

It should be noted that this inter-cyme interval, of 17.5 mm, in average, is virtually identical for the ecotypes “Kali,” “Mrs. Burns,” “Sweet Dani,” and “Lime Thai” – regardless of plant size.

For the record, in Ocimum basilicum, this inter-cyme interval varies from 9 mm to 16 mm, with an average of 12.5 mm.

It should also be noted that the shape of the shield – particularly at the junction with the peduncle – allows Ocimum basilicum to be distinguished from Ocimum americanum var. pilosum.

Ocimum americanum var. americanum – namely the different ecotypes that I have grown this year and in 2022 – are approximately 35 to 55 cm tall in the garden.

These are the following ecotypes: “Malawi Camphor”, “African” (Kokopelli) as well as various ecotypes, from GRIN, originating in Zambia, with a chemotype Camphor or Eucalyptol.

The flower stems are, on average, 18 to 20 cm long in “Malawi Camphor” and other Zambian ecotypes. As for the dry calyxes, the largest are about 3.5 mm wide- and are therefore smaller than those of Ocimum bisabolenum.

The interval between the “cymes” (6 flowers simulating a whorl around the stem) is very small. Thus, there are up to 35 cymes on a 21 cm floral stem in Zambian Camphor basil – with an average interval of 6 mm.

Photographs of Leaves and Fruiting Calyxes of the various main species of Ocimum

Ocimum bisabolenum

Ocimum kilimandsharicum

Ocimum americanum var . pilosum

Ocimum americanum var. americanum

Ocimum basilicum

Ocimum tenuiflorum