Summary

History of my 3 sterile Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants crossed with X – with orange pollen

History of my 4 sterile Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants crossed with X – without pollen

Ongoing discoveries involving another wave of Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants crossed with X

Caveat. In this Third Report “Basilics 2025”, I use both the species name, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, and its name in India, “Kapura”.

In India, Ocimum kilimandscharicum got its name “Kāpūra” from the term for “Camphor” in Marathi. But nothing is simple in this gigantic country. “Kapura” is also the term for the species Camphora officinarum in Kannada and Marathi; as well as the term for Limnophila indica in Odia; and also the term for the species Cinnamomum camphora and Ehretia laevis in India.

Furthermore, among the Tantric Pagans of Shaktism in India, Kāpura is one of the 16 Siddhas, one of the 16 “Instructors” – and “Liberators”…

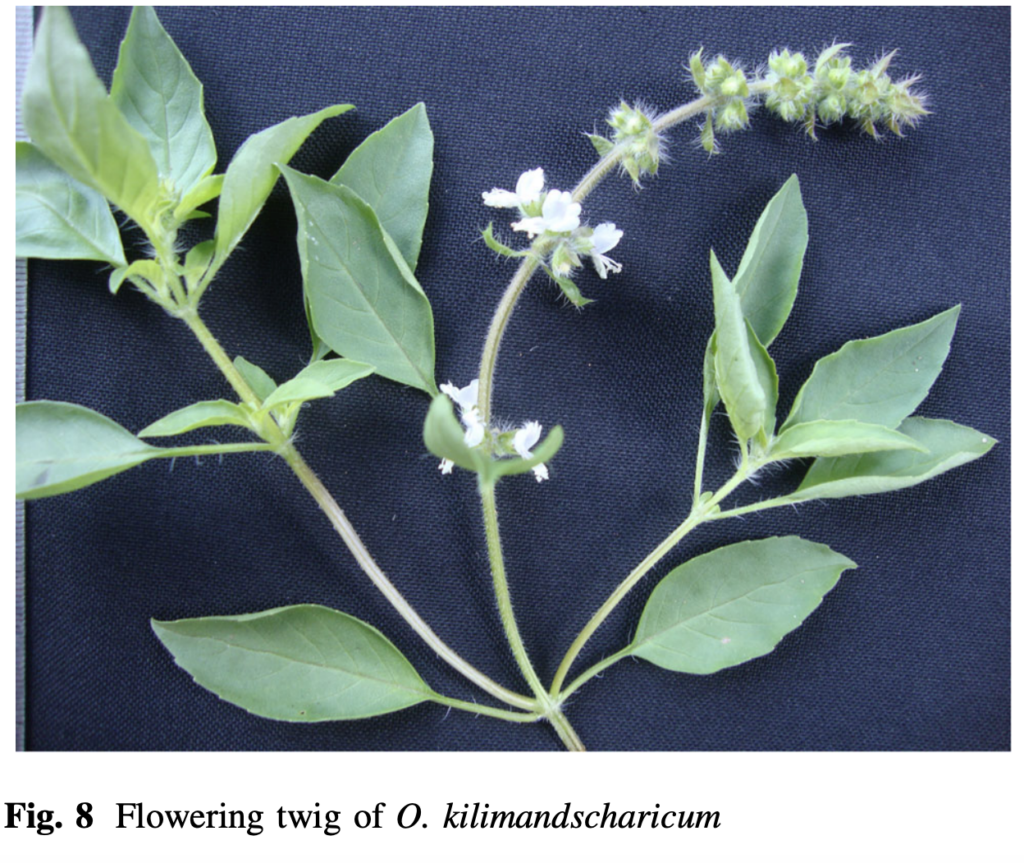

The species Ocimum kilimandscharicum is characterized by a predominant self-sterility… and, therefore, an almost obligatory cross-pollination.

The first of my main discoveries, this summer of 2025, is that the species of Basil, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, is mostly self-sterile – and therefore under a regime of almost mandatory allogamy.

The second point is that it seems established that Ocimum kilimandscharicum can cross spontaneously… and often.

Thus, Ocimum kilimandscharicum easily lends itself to the games of interspecific genetic flows of the Gaïan Lottery!

Indeed, this summer, in our garden, I just discovered that the first floral stems harvested from the unique Ocimum kilimandsharicum plant that germinated, accession PI 652052, from the GRIN/USDA (wrongly presented by their taxonomists as Ocimum americanum) bear almost no seeds – whereas this plant was growing under an insect-proof breeding tent… thus, free of insects.

Today, moreover, it remains to be determined whether the self-sterility of Ocimum kilimandscharicum occurs at the plant level (as with Cabbages or Sunflowers) or at the level of the individual flower (as with Carrots).

The only way to find out is to cultivate a Kapura under a tent, covered with a mosquito net, accompanied by a small hive of pollinating insects inside. If the self-sterility of Ocimum kilimandscharicum is at the plant level, there will not be, really, any more seed production, despite inter-floral pollination, than in a situation without insects.

This means that we have produced certified organic seeds of Ocimum kilimandscharicum – with Terre de Semences and the Kokopelli Association – since 1994 without ever being aware of its authentic reproduction system. The same applies to all our organic seed colleagues in Europe and, especially, in North America – for even longer.

In fact, when seed growers cultivate a hundred or several hundred plants of Ocimum kilimandscharicum, it is impossible for them to discover whether this species is almost entirely self-sterile due to the fact that pollinating insects will remain on site – intoxicated by an abundance of nectar and pollen. It should be noted that statistically speaking, such a species – now proven to be strictly allogamous and capable of interspecific hybridization – will have very few non-conforming seeds, due to its extreme concentration and the large number of seed-bearing plants.

We have followed, for about thirty years, the principle of self-fertility and non-interspecific hybridization, in the major species of Ocimum, and the principle of certain intraspecific hybridization, in Ocimum basilicum and Ocimum americanum. Wrongly, obviously, in the case of Ocimum kilimandscharicum!

The most evident manifestation of this absence of interspecific hybridization, among the major species of Ocimum, is the strict impossibility of transferring the resistance genes to basil downy mildew from the species Ocimum bisabolenum, Ocimum americanum, Ocimum tenuiflorum, and Ocimum gratissimum to Ocimum basilicum.

As for Ocimum kilimandscharicum, this species is not favored by researchers for fighting against downy mildew, due to its high camphor content – at least, that of the most commercially marketed ecotypes.

I would like to clarify, again, that I introduced Ocimum kilimandscharicum – in the form of certified organic seeds – in France and Europe, in 1994, with the first catalog of Terre de Semences. Ocimum kilimandscharicum was part of our range of organic seeds – nearly 600 accessions. We have never found information on the floral and reproductive biology of this species.

Clearly, the three only studies related to this issue – published online and presented below – date back to 2018, 2020, and 2023. However, one must still find them!

Moreover, a professional seed grower cultivating a hundred, or a few hundred, plants of Ocimum kilimandscharicum will not be able to discover the almost obligatory allogamy characterizing this species because it will predominantly manifest only in intra-specific allogamy in his field – namely, between plants of the same species.

As a reminder. A plant can be strictly self-fertilizing but, nonetheless, under a regime of potential outcrossing. This is the case with Tomato, Pepper, Lettuce, Bean, Okra, etc., etc. – and with Basil, Ocimum basilicum.

On the other hand, in our gardens this year, it is an intra- and inter-specific allogamy, given the few Kapura plants (about twenty) cultivated among hundreds of other plants of various cultivars or ecotypes of the following species: Ocimum basilicum, Ocimum bisabolenum, Ocimum americanum, Ocimum tenuiflorum, Ocimum gratissimum, Ocimum carnosum, and Ocimum campechianum.

Our balcony, on the upper floor, is reserved for very large, sterile plants of Kapura, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, crossed with X – some with orange anthers and pollen, others with white or beige anthers but without pollen. Thus, I have been able to observe daily the constant influx of foraging and collecting insects – and therefore, pollinators – from dawn until dusk. The same goes for the hundreds of Basil plants in the garden, of 85 types: they are also very visited…

This means that these Basil flowers release their nectar for very long hours. In addition, these Basil plants attract a very wide variety of pollinators: honeybees, wasps, bumblebees, ground bees, butterflies, etc.

This means that the same flower is visited multiple times during its anthesis.

It should also be noted that the very large plants, all sterile, of Ocimum kilimandscharicum, crossed with X, on the balcony, are extremely visited because they are of a generous growth amplitude and a continuous flowering – especially since they do not produce seeds.

Last month, I incorrectly mentioned that there were no studies on the reproductive mechanisms of Ocimum kilimandsharicum. To validate my discovery regarding its almost self-sterility, I therefore set off again in search of information on the web… and I indeed found some in three studies:

It should be specified, above all, that the species Ocimum kilimandscharicum is very uncommon in gardens and very little investigated by researchers… because research is expensive. For example, a search on the US Pubmed website shows 1500 references for Ocimum basilicum, 847 for Ocimum tenuiflorum, and 47 for Ocimum kilimandscharicum! That is why we had to wait until 2018 for these three studies, on the reproductive processes characterizing Ocimum kilimandscharicum, to be published.

1. A Nigerien study, from 2018, highlighted that the seed production in Ocimum kilimandscharicum is higher when the diversity of pollinating insects is abundant. At 50 meters from the forest, the diversity of insect species is three times greater than at 220 meters – and the number of insects is double. LINK

2. A study from Bangalore, in 2020, highlighted, in Ocimum kilimandscharicum, the lower amount of seeds in cage pollinations compared to open pollination gardens or pollination sites by the local bee Apis cerana. LINK

3. A Kenyan study, from 2023, highlighted that plants of Ocimum kilimandscharicum growing under veiled pollination cages – hence, in strict autogamy – produced 103 seeds while those growing in gardens, under open pollination, produced 22,960. LINK

Namely, about 230 times more in open pollination than in covered cages. This indicates that there is indeed a regime of nearly obligatory allogamy in Ocimum kilimandscharicum – whose self-sterility, according to this study, is 99.56%.

Then, just after posting – and translating into English – my second report “Basil 2025”, I informed Peter Nick, the director of the Botanical Institute of Karlsruhe, of my discovery, who asked me if I thought there was a delay between the maturity of the stamens and that of the style in Ocimum kilimandscharicum.

It was then that I remembered my sequence of photos, taken in 2022, of the opening of an Ocimum kilimandscharicum flower. It is clearly visible there that the flower blooms with stamens completely devoid of pollen, while, as soon as it opens, an insect rushes to the bottom of the corolla to extract nectar – thus signaling the maturity of the female reproductive organ.

This is a process known as “proterogyny“ by which female cells mature before male cells to prevent self-fertilization.

I did not stop at this sequence of photographs and I went on to dissect a few floral buds ready to bloom in order to check that they were characterized by the same protogynous reproductive regime. And I took a few photographs of them.

Note that my sequences of photographs from the first phase of anthesis in Ocimum basilicum (LINK), highlight the presence of mature pollen from the moment the flower opens. The same is true for Ocimum americanum (LINK) with exceptions, for Ocimum americanum sp. americanum, some ecotypes of which are highly self-sterile.

I even managed to capture the opening of flowers of my 3rd Ocimum kilimandscharicum hybrid (Kapura X. OR. 04/2025) – which emerged in the garden this summer 2025 – featuring orange-colored anthers and orange pollen. I was also able to observe the same phenomenon of orange-colored anthers (sometimes very light) but without pollen, at the beginning of anthesis.

One of the photographs highlights two anthers with ripe pollen while the other two anthers are still virgin.

It remains to be seen if this 3rd hybrid Ocimum kilimandscharicum, with orange pollen, will be more fertile than my two other large completely sterile plants of 2024. Apparently, in these hybrid Ocimum kilimandscharicum, the presence of nectar and orange pollen does not necessarily equate to fertility.

It will also remain to be determined, next year, whether the few seeds harvested from Ocimum kilimandsharicum “PI 652052” are fertile.

In provisional conclusion, this almost total self-sterility in Ocimum kilimandsharicum explains even better, of course, the inclination of this species to be courted by the very numerous buzzing pollinator insects moving from one species of Ocimum to another.

Addendum dated October 15, 2025. It is clear that this self-sterility is not total. Yesterday, I had the opportunity to photograph the beginning of the opening of a Kapura flower whose stamens were covered with orange pollen. In this sequence, a butterfly rushes into the flower 12 seconds later – while the stamens are not yet fully open – and remains there foraging for 52 seconds.

History of my 3 sterile Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants crossed with X – with orange pollen

During the summer of 2024, two Basil plants appeared in my garden, spontaneously, with pollen and anthers of orange color – as characterized by Ocimum kilimandscharicum. However, they had very different leaves and a Cinnamon scent – namely, a predominant chemotype in Methyl cinnamate.

Ocimum bisabolebum, also, has orange/red brick colored pollen but, apparently, it does not seem to be involved in all these spontaneous crossings.

The first plant – which I named Kapura X. OR. 01/2024 (OR meaning Orange Pollen) – measured nearly 1 meter in amplitude by autumn 2024, after having emerged, spontaneously, in a path with very compact soil covered in olive bark. At the end of November, I tried to extract it but could only unearth a small part of its root system… and it did not survive the approach of winter.

This plant was very exceptional in that the majority of its branches bore purple flowers while a minority bore white ones – all with pollen and orange anthers.

In fact, the situation was a bit more complex in that the white flowers were borne by stems and calices of a purplish color that turned green at full maturity. As for the purple flowers, they were borne either by stems and calices of a purple color (staying purple); or by stems and calices of a purplish color that turned green at full maturity.

To date, I personally know of only one species producing plants with branches, for example, with yellow flowers, red flowers, and flowers streaked with red and yellow: Mirabilis jalapa, the Marvel of Peru.

In fact, there was no difference with the hybrid called “Magic Mountain”… except for the exceptional presence of the two types of flowers according to the branches.

The second, later – which I named Kapura X. OR. 02/2024 – had less amplitude and grew in a pot because I was able to dig it up from the garden. It survived the winter on a wind-swept balcony, at temperatures of about -7° and, above all, during four days of very frosty fog. Its corolla is relatively white, with a slight purple tint. The pistil is purple but the stamens are white.

Today, it has more than a meter of amplitude. We are in September and it has been blooming since February. You just need to cut back its long stems, which are non-fruiting calyxes, in order to encourage it to branch out in all directions.

The first Kapura X. OR. 01/2024 plant survived through a single cutting that we managed to save and transplant in January. I named it Kapura X. OR. 03/2024. Like its mother plant, it is huge but, unfortunately, at least for now, it has not retained the exceptional double coloring of the flowers. In fact, it only has white flowers carried by stems, and calyxes, that are purplish in color becoming green at full maturity. It is worth mentioning that its flower stems are very long, reaching 34 cm.

In the daughter plant, obtained from cuttings, only part of the genetic information has been preserved.

This would mean that in the mother plant, Kapura X. OR. 01/2024, the genetic information, particularly coding for flower color, was different depending on the type of branch.

During the summer of 2025, another hybrid Kapura appeared spontaneously in the melons. I unearthed it and repotted it in order to study its evolution. I named it Kapura X. OR. 04/2025.

It already has a strong amplitude. Its anthers and pollen are characterized by an orange color. However, unlike other Kapura with orange pollen, its floral tops are free of purple coloring and, therefore, anthocyanins. Its long leaves, which are very slightly serrated, could suggest that it is a cross with Ocimum americanum sp. americanum.

The sequence of photographs below concerns Kapura X. OR. 04/2025:

It is worth noting that these three crossed Kapuras, with orange pollen, are characterized by the same regime, of protogynous floral biology, as authentic Kapuras. Indeed, at the beginning of anthesis, the stamens are completely devoid of pollen.

On the other hand, the reproductive processes are disabled because these three crossed Kapuras are totally sterile – despite the presence of pollen and an abundance of nectar.

Given the amplitude of the plants and the chemotype Cinnamon, I suspect that these are spontaneous crossings involving Ocimum kilimandscharicum and Ocimum basilicum. Why not involving Ocimum americanum? Because so far, there are only proven examples of crossings between Ocimum kilimandscharicum and Ocimum basilicum.

It is one of the themes I will be working on during the summer of 2026: the potential for spontaneous crossings involving Ocimum kilimandscharicum and Ocimum americanum – in particular, the Euro-Asian ecotypes of the Citral type of Ocimum americanum sp. pilosum..

Indeed, this would not be the first case since the agronomic center of Lucknow, in India, has developed new cold-resistant lines from natural hybrids involving these two species, growing in their gardens around 2010. And this is without mentioning the introduction of sterile lines such as “Magic Mountain F1”, “Magic White F1” and “African Blue”.

“African Blue” would be a hybrid – which appeared spontaneously in Ohio in the early 1980s – between Ocimum kilimandscharicum and “Dark Opal”, Ocimum basilicum.

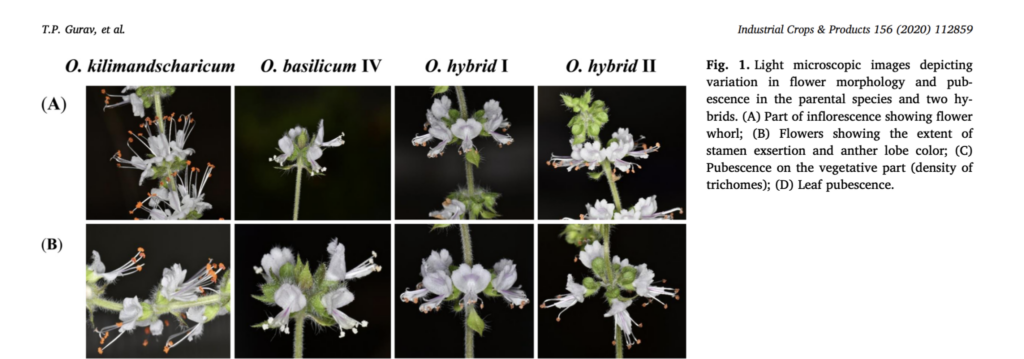

According to the study, from Lucknow, in 2020, “Generation of novelties in the genus Ocimum as a result of natural hybridization: A morphological, genetical and chemical appraisal”, [45] the two hybrids presented have orange-colored pollen – but less bright than that Ocimum kilimandscharicum’s one.

According to the authors: « These two novel Ocimum hybrids exhibited intermediate morphological features of two parental species. Inter simple sequence repeats (ISSR) analysis and DNA barcoding with the plastid non-coding trnH-psbA intergenic spacer region reafrmed unambiguous parental identifcation and dif- ferentiation of these natural hybrids from other available Ocimum species. Consequently, gas chromatography- mass spectrometry-based metabolite profling of two hybrids identifed them as specifc chemotypes with the presence of a unique blend of specialized metabolites from the parental species, which are either rich in terpenes or phenylpropanoids. Additionally, expression analysis of key genes from terpenoid and phenylpropanoid pathways corroborated with diferential metabolite accumulation. Thus, these two Ocimum hybrids represented the novel chemotypes, which could be useful in commercial cultivation to produce novel essential oil and bioactive constituents».

In conclusion. In my essay from September 2024, “About my discovery of spontaneous crosses between Ocimum basilicum and Ocimum kilimandscharicum… with orange pollen,” I had hypothesized that these were Ocimum basilicum plants crossed with Ocimum kilimandscharicum. In fact, they are truly Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants crossed with X. Why? Due to the shape and size of their calixes, which are all similar – measuring 3 to 3.5 mm in width.

History of my 4 sterile Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants crossed with X – without pollen

I sowed, in the spring of 2025, seeds of Kapura, from my very diverse basil garden in 2022, as well as seeds from a plant that appeared spontaneously during the summer of 2024, along with seeds from the Kokopelli Association – produced in 2017 and that I had already cultivated during the summer of 2022.

I then kept about twenty Kapura seedlings to cultivate them in pots or in the garden. This resulted in a few crossbred plants that were deformed and weak; about ten normal plants; and four crossbred plants that grew beautifully on my balcony.

These four crossed plants, I named them SP – for Without Pollen (Sans Pollen in French):

Kapura X. SP. 01/2025.

Kapura X. SP. 02/2025.

Kapura X. SP. 03/2025.

Kapura X. SP. 04/2025.

These four crossed abnormal plants appear less camphoraceous at first glance. Three of these plants are characterized by hyper-branching – two of which have very short branches: the main stems produce 12 to 24 floral sub-stems that are 6 to 10 cm long.

Kapura X. SP. 04/2025 and Kapura X. SP. 03/2025 are characterized by hyper-branching with very short floral stems – and, moreover, for Kapura X. SP. 03/2025, by a brown coloration that completely turns green at the end of their flowering.

On the other hand, the one with a normal branching, Kapura X. SP. 01/2025, has floral stems reaching 38 cm in length. This is a record because, this year, the largest I measured were 36 cm in the Turkish ecotype of Lemon Basil, “Esfahan”, Ocimum americanum sp. pilosum.

In fact, what mainly characterizes these crossed Kapuras is their exceptional ability to occupy all the available space: for example, by extending branches almost horizontally, sometimes reaching a length of 80 cm.

Furthermore, they have flowers with relatively short stamens and anthers that are white/gray/beige – and sometimes a very light orange – completely lacking pollen… instead of bright orange anthers, and bright orange pollen, and very long stamens.

During the summer, I noticed that these four plants are all sterile as well – namely, that their floral stems are perfectly developed but with fruiting calyces that remain empty.

In light of the vastness of insects that visit them due to the abundance of nectar flow – and, therefore, the likely activation of the female reproductive system – one might assume it would be otherwise… but that is not the case.

These four crossed Kapuras plants are characterized, therefore, by a total absence of pollen, an abundance of nectar, and a total absence of seeds.

Are there ecotypes of Ocimum kilimandscharicum with white anthers and white pollen? The only mention of light-colored pollen for this species is found in the 2017 study, “Diversity of the genus Ocimum (Lamiaceae) through morpho-molecular (RAPD) and chemical (GC–MS) analysis”. Their authors assert that «Ocimum kilimandscharicum has brick red or gray colored pollen which was entirely different from other genotypes.» LINK.

On the other hand, there is a study from 2015 titled “Ocimum kilimandscharicum Guerke (Lamiaceae): A New Distributional Record for Peninsular India with Focus on its Economic Potential”, which comments on the discovery of Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants in two sites of different agro-ecological zones of Odisha in India. LINK.

The photographs presented there highlight plants with somewhat different foliage and, above all, flowers with white anthers. In these photographs, the pollen is unfortunately not visible, but the authors mention the presence of seeds – and thus, of fertile plants.

Would there be, then, natural hybrids, but fertile, involving Ocimum kilimandscharicum in certain regions of India?

In fact, these plants look very similar to mine – both in terms of foliage and shape. One of the photographs even shows a very frail plant with small leaves, like the one I had this year.

This spring, unfortunately, I did not keep track of all my Ocimum kilimandscharicum seedlings according to the various seed sources… because I did not imagine the nature of my discoveries regarding this species.

For example, the plant Kapura X. SP. 03/2025 comes from a mother plant of Ocimum kilimandscharicum – which appeared spontaneously during the summer of 2024 – that I deem authentic, at least from a phenotypic point of view.

I suspect, however, that some hybridized plants of Ocimum kilimandscharicum may have resulted from a spontaneous crossing during the 2017 season, at Maryse’s place, who was a producer for Association Kokopelli, where she produced 337 grams of seeds as well as nearly a kilo of seeds from the Ocimum basilicum ecotype, “Mrihani” – which represents a substantial opportunity for crossings involving these two species due to the very large number of seed-bearing plants… and the irresistible attraction for pollinators from all spheres.

This proximity, at Maryse’s seed production farm, between “Mrihani” and Kokopelli’s camphor ecotype of Ocimum kilimandscharicum – which may be fatal in terms of seed purity – that I have discovered, recently, in a seed database, is a very fascinating synchronicity!

On this subject, even before discovering his risky cultivation situation in 2017, I had mentioned, with the director of the Botanical Institute of Karlsruhe, Peter Nick, the hypothesis that an ecotype from East Africa, the Kilimanjaro Basil, Ocimum kilimandscharicum, may have crossed with the local ecotype of Zanzibar of Ocimum basilicum – referred to as “Mrihani”… from the Arabic term “Reihan“ for Basil. This spontaneous cross might be the source of its complete, and unique in the world, resistance to Basil Downy Mildew.

Some geneticists refer to plant immune receptors – the leucine-rich repeat proteins NLR – or multifunctional receptor-like kinases to explain this exceptional resistance to Peronospora belbahrii… but this, in no way, indicates the source of the genetic transfer or the evolutionary emergence.

This hypothesis is interesting insofar as Zanzibar is located, in the Indian Ocean, almost directly opposite Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Moreover, coincidentally, the Basil downy mildew, Peronospora belbahrii, is also native to the area of Tanzania and Uganda – in 1932.

In conclusion, in terms of the integration of genes for resistance to Basil Downy Mildew, into edible Basil cultivars of Ocimum basilicum, the Ocimum kilimandscharicum X Ocimum basilicum pathway could prove fruitful. This is especially true if less “camphoraceous” ecotypes of Ocimum kilimandscharicum are available, as consumers are not fond of camphor on their plates. There are, in Africa, for example, other ecotypes of which are devoid of, or very low in, Camphor. Such is the case for the GRIN/USDA ecotype, PI 652052, which had for chemotype, in one analysis: Estragol 31%, Camphor 12%, Eucalyptol 11%, Eugenol 9%.

Clearly, Ocimum kilimandscharicum loves to flirt! And given my first spontaneous cross involving Ocimum basilicum x Ocimum kilimandscharicum, producing branches with white flowers and branches with purple flowers, it is certain that this species behaves playfully – considering the standardized and official claims. Who has heard of Basil plants with tho kind of flowers?

It is certain that the seeds of Ocimum kilimandscharicum must be produced away from any cultivar of Ocimum basilicum – and, with all due caution, away from any other species of Ocimum.

… … and away from bees carrying, possibly, pollen from Basil from the surrounding gardens… because bees (domestic and wild) as well as bumblebees love and indulge in the royal pollen of Basil.

In another conclusion, if Ocimum kilimandscharicum spontaneously crosses with Ocimum basilicum, and vice versa, it is quite possible that Ocimum kilimandscharicum could cross with other species of Ocimum – and vice versa.

Ongoing discoveries involving another wave of Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants crossed with X

I sowed, during the summer of 2025, another wave of seeds of Ocimum kilimandscharicum from the plants cultivated in the spring of 2025 (Kapura 2025), which originated from the unique mother plant (Kapura 2024) that appeared spontaneously during the summer of 2024.

These two generations seem authentic… at least from a phenotypic point of view: overall appearance, leaves, flowers, color of the pollen…

Of the 30 seedlings that I replanted from the seed trays, I kept 20 which I transferred to larger pots with good potting soil. The results were very surprising in that 18 of the Kapuras are clearly crossbred with only 2 Kapuras that, at first glance, seemed authentic – but they are not. Indeed, their flowers do have orange pollen but they are small and light purple in color. This means that this sowing resulted in 100% crossbred plants.

All these crossed plants are characterized by a generous amplitude – and a much faster development than in authentic Kapuras. Some are characterized by a purple coloration in the floral tips, stems, and leaf veins.

I was so surprised by the extent of these crossings that I sowed, again, last week, trays (of 72 cells) of Ocimum kilimandscharicum seeds coming from Kapura 2024 and Kapura 2025.

Indeed, I am extremely intrigued by the phenotypic similarity of the crossed plants obtained in these seedlings. Indeed, the size of the leaves varies somewhat, as well as the color of the emerging floral buds, but the overall growth habit is very similar. It is as if the pollen, responsible for the spontaneous crosses, comes from the same donors.

In my First Report, published on July 12, 2025, I had written: «This year, I am even going so far as to plant a “Cinnamon” or “Licorice” Basil together with an Ocimum kilimandscharicum in the same pot in order to play the lottery with the Archetype Ocimum! Why? Because it seems that my first two spontaneous crosses involved the chemotype “Methyl Cinnamate” in Ocimum basilicum.»

Thus, during the summer, I had 5 Ocimum kilimandscharicum plants surrounded by 7 Basils “Cannelle”, “Anis”, et “Réglisse”, Ocimum basilicum – from Kokopelli – namely, basically, the same type of Basil called “Cinnamon”.

It would seem, therefore, a priori, that some of these crossed Kapuras could be with these Basils of the “Cinnamon” type – whose floral tops have purple coloration.

Why a priori? Because sometimes, their flowers were only a few centimeters apart in insect flight. Indeed, I have observed in our region that many pollinators jump from one plant to another – in search of pollen, nectar, or other resinous substances – without worrying too much about species! This is even truer in a very dry biotope: insects follow the flow and the scents of pollen and nectar… and thank whoever is responsible!

It is only if there is a certain number of Basil plants, of the same ecotype or cultivar, in the same space that bees, for example, will stay there: this is how foraging bees on Ocimum bisabolenum carry brick-red pollen baskets… when Besobila plants are abundant.

In a few weeks, I will know the nature of the seedlings from my last batch of Kapura 24 and Kapura 2025 sowing.

My great pleasure would be, of course, to discover fertile crossbred Kapura plants – with viable seeds!

Pending this auspicious day, I will, during the 2026 season, delve into the subject of interspecific crossings in Ocimum kilimandscharicum, potentially involving Ocimum americanum or Ocimum bisabolenum.

November 2025 addendum: here are a few pictures of crossed Kapura, among many others, with their huge and magnificent purple or green leaves.

It therefore seems very easy for gardeners to obtain hybrid plants of Ocimum kilimandscharicum. In a garden, it is sufficient to cultivate a few of them completely isolated from each other – and surrounded by many other basils of Ocimum basilicum. Due to their self-sterility, the plants of Ocimum kilimandscharicum are then statistically much more pollinated by male pollen coming from the surrounding plants of Ocimum basilicum.

Xochi.

Here is a sequence of photographs (of Xochi) illustrating the delicate blossoming of a Kapura flower crossed with X – with purple hues – and also illustrating my patience as one must wait for the flower’s willingness, which then opens in the span of 30 seconds. In Homage to Beauty!